{{himg[1]}}

Furniture, Clocks, Decorative and applied arts

As we enter the Furniture, Clocks, Decorative, and Applied Arts gallery, our attention is drawn to a beautifully crafted rosewood cabinet adorned with paintings and gilded framing elements. The question arises: is this a piece of Oriental art or a European furniture item?

In the late 17th century, the East India Company's imports fr om the East sparked a surge in the popularity for Chinese decor items in Europe. This led to the emergence of the "chinoiserie" trend, wh ere interior objects were stylized to resemble Chinese art. Despite the distinct European forms reminiscent of the Empire style, upon closer inspection of the exquisite traditional Chinese motifs of trees and rocks, one might wonder: could this be a Chinese bookcase? No, it is indeed chinoiserie. The narrative depicted on the bookcase involves a nighttime rendezvous. A nobleman, even at night, is shielded from the sun by his servants' fans, rushing to meet a gesturing woman. Her attendants hold a paper, a guest list, and the shape of the keyhole resembles a lantern, the famous red light illuminating the entrance to a "spring home" in China. Completing this scene is a shell (framed in the painting), a European symbol of love and the feminine principle, echoing the theme of Venus's birth. Since Marco Polo's time, Europeans have been acquainted with many Chinese traditions, yet much remained mysterious, shrouded in exotic allure. The fusion of Empire style and chinoiserie reflects the characteristic historian, a trend popular in mid-19th century Europe.

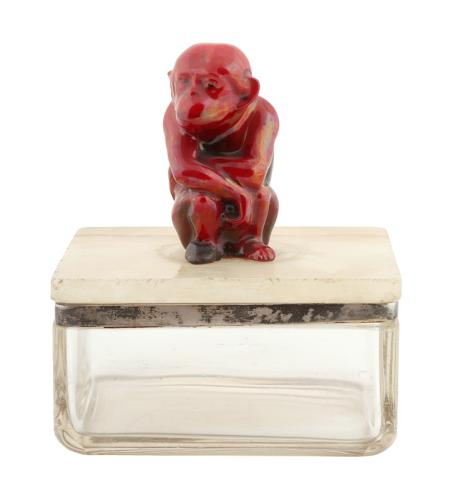

Taking a few virtual steps, we have the unique opportunity to compare a European piece of furniture stylized after Chinese art with an authentic Chinese cabinet. The cabinet with hibiscus features the succinct volume characteristic of Eastern art: its simple form is akin to an inverted chest or box. Handles on the sides allow two individuals to easily lift and move it. The "box" rests on an elegant base with curved legs — a contrast that captivates and intrigues a European observer. The stylistic mismatch between the upper and lower parts of the cabinet is concealed by exquisite decoration. Plant motifs cover the entire surface of its doors, upper, and side walls. Hibiscus, a symbol of sun and joy in Chinese culture, is depicted in a harmonious blend of red, gray, gold, and brown, creating the illusion of light playing on leaves, flowers, and buds. Brass overlays, such as hinges, corners, and lock framing, also feature finely detailed intertwined leaf patterns. The simplicity and conciseness of the cabinet's form are the only reminders of a "box"; otherwise, it is a marvelous and delicately crafted work of art. The European fascination with Eastern exoticism is further accentuated in this room by a Japanese knife with herons (interior details, of course, must align with the overall concept) and a box made in England with a monkey.

Decorative and applied arts, more than any other form, quickly respond to changing tastes, fashions, and styles. The years 1830-1880 marked the period of historicism, during which artists borrowed features from various styles, often combining them in a single work. The clock from 1840 pays homage to rococo (mid-18th century style). An idyllic pastoral motif of a young shepherd and shepherdess in the lap of nature conveys youth, beauty, and harmony with the world. The composition is complemented by a touching detail: the young man assembled a bouquet for his beloved, placing it in his own hat.

In the mantel clock composition, the triangular base, akin to rococo, transforms waves and shells into leaves, shoots, and buds. A garland of flowers adorns the girl's head. Youthful and beautiful, she holds a snake in her right hand and a dove in her left. In a heartfelt impulse, the child saves the bird, risking its own life. The viewer is drawn to the naive feelings, the purity of childish thoughts, and the desire for closeness to nature. However, this is not a nod to rococo; the girl is the central figure of the composition, not part of a whimsical pastoral world. The position of the figure, the child's dress reminiscent of a Greek chiton, and the abundance of gilding indicate that this work of historicism is inspired by the Empire era.

Empire (high neoclassicism), translated from French as the "imperial" style, was popular in Europe in the first quarter of the 19th century. Its emergence was associated with the rule of Napoleon Bonaparte, unimaginable military and political successes, and the elevation of France. While similar to early and mature neoclassicism, the Empire significantly increased the level of solemnity and grandeur, hence the abundance of gold combined with strict forms. A characteristic example of Empire style in this room is the pair of candelabra: a bronze figure of the goddess of victory Nike in a chiton hovers above us, illuminating and sanctifying the room simultaneously. References to the Empire style can also be observed in the paired vases (depicting the offering of fruits of labor and art to the gods) and the ceramic urn.

From the time of Alexey Venetsianov, pastoral themes were not foreign to Russian art. Girls in porcelain miniatures, in simple clothing and headgear, exude tenderness and charm. However, the gilded framing reminds the viewer that these are not poor shepherdesses but noble ladies paying homage to fashion.

At the end of the 19th century, the Art Nouveau style became extraordinarily popular. In this style, plant ornaments not only adorn art objects but also sprout into their very essence, defining the specificity of volumes and forms. Signs of Art Nouveau can be seen in the showcase, the vitrine, the looking glass, the rose-shaped candlesticks, and even the handles of the tray — the plant world captivates decorative and applied arts. Russian art is responsive to all European trends, but upon closer inspection, for example, in the forms of a decorative plate, one can discern a unique echo of Russian fairy tales in the unity of historicism and Art Nouveau ornaments.

In the late 17th century, the East India Company's imports fr om the East sparked a surge in the popularity for Chinese decor items in Europe. This led to the emergence of the "chinoiserie" trend, wh ere interior objects were stylized to resemble Chinese art. Despite the distinct European forms reminiscent of the Empire style, upon closer inspection of the exquisite traditional Chinese motifs of trees and rocks, one might wonder: could this be a Chinese bookcase? No, it is indeed chinoiserie. The narrative depicted on the bookcase involves a nighttime rendezvous. A nobleman, even at night, is shielded from the sun by his servants' fans, rushing to meet a gesturing woman. Her attendants hold a paper, a guest list, and the shape of the keyhole resembles a lantern, the famous red light illuminating the entrance to a "spring home" in China. Completing this scene is a shell (framed in the painting), a European symbol of love and the feminine principle, echoing the theme of Venus's birth. Since Marco Polo's time, Europeans have been acquainted with many Chinese traditions, yet much remained mysterious, shrouded in exotic allure. The fusion of Empire style and chinoiserie reflects the characteristic historian, a trend popular in mid-19th century Europe.

Taking a few virtual steps, we have the unique opportunity to compare a European piece of furniture stylized after Chinese art with an authentic Chinese cabinet. The cabinet with hibiscus features the succinct volume characteristic of Eastern art: its simple form is akin to an inverted chest or box. Handles on the sides allow two individuals to easily lift and move it. The "box" rests on an elegant base with curved legs — a contrast that captivates and intrigues a European observer. The stylistic mismatch between the upper and lower parts of the cabinet is concealed by exquisite decoration. Plant motifs cover the entire surface of its doors, upper, and side walls. Hibiscus, a symbol of sun and joy in Chinese culture, is depicted in a harmonious blend of red, gray, gold, and brown, creating the illusion of light playing on leaves, flowers, and buds. Brass overlays, such as hinges, corners, and lock framing, also feature finely detailed intertwined leaf patterns. The simplicity and conciseness of the cabinet's form are the only reminders of a "box"; otherwise, it is a marvelous and delicately crafted work of art. The European fascination with Eastern exoticism is further accentuated in this room by a Japanese knife with herons (interior details, of course, must align with the overall concept) and a box made in England with a monkey.

Decorative and applied arts, more than any other form, quickly respond to changing tastes, fashions, and styles. The years 1830-1880 marked the period of historicism, during which artists borrowed features from various styles, often combining them in a single work. The clock from 1840 pays homage to rococo (mid-18th century style). An idyllic pastoral motif of a young shepherd and shepherdess in the lap of nature conveys youth, beauty, and harmony with the world. The composition is complemented by a touching detail: the young man assembled a bouquet for his beloved, placing it in his own hat.

In the mantel clock composition, the triangular base, akin to rococo, transforms waves and shells into leaves, shoots, and buds. A garland of flowers adorns the girl's head. Youthful and beautiful, she holds a snake in her right hand and a dove in her left. In a heartfelt impulse, the child saves the bird, risking its own life. The viewer is drawn to the naive feelings, the purity of childish thoughts, and the desire for closeness to nature. However, this is not a nod to rococo; the girl is the central figure of the composition, not part of a whimsical pastoral world. The position of the figure, the child's dress reminiscent of a Greek chiton, and the abundance of gilding indicate that this work of historicism is inspired by the Empire era.

Empire (high neoclassicism), translated from French as the "imperial" style, was popular in Europe in the first quarter of the 19th century. Its emergence was associated with the rule of Napoleon Bonaparte, unimaginable military and political successes, and the elevation of France. While similar to early and mature neoclassicism, the Empire significantly increased the level of solemnity and grandeur, hence the abundance of gold combined with strict forms. A characteristic example of Empire style in this room is the pair of candelabra: a bronze figure of the goddess of victory Nike in a chiton hovers above us, illuminating and sanctifying the room simultaneously. References to the Empire style can also be observed in the paired vases (depicting the offering of fruits of labor and art to the gods) and the ceramic urn.

From the time of Alexey Venetsianov, pastoral themes were not foreign to Russian art. Girls in porcelain miniatures, in simple clothing and headgear, exude tenderness and charm. However, the gilded framing reminds the viewer that these are not poor shepherdesses but noble ladies paying homage to fashion.

At the end of the 19th century, the Art Nouveau style became extraordinarily popular. In this style, plant ornaments not only adorn art objects but also sprout into their very essence, defining the specificity of volumes and forms. Signs of Art Nouveau can be seen in the showcase, the vitrine, the looking glass, the rose-shaped candlesticks, and even the handles of the tray — the plant world captivates decorative and applied arts. Russian art is responsive to all European trends, but upon closer inspection, for example, in the forms of a decorative plate, one can discern a unique echo of Russian fairy tales in the unity of historicism and Art Nouveau ornaments.